I only had 3 things in my “bucket list” on my last trip to Europe: (1) talk to locals, (2) talk to fellow travelers, and (3) buy a book from a bouquiniste.

.

.

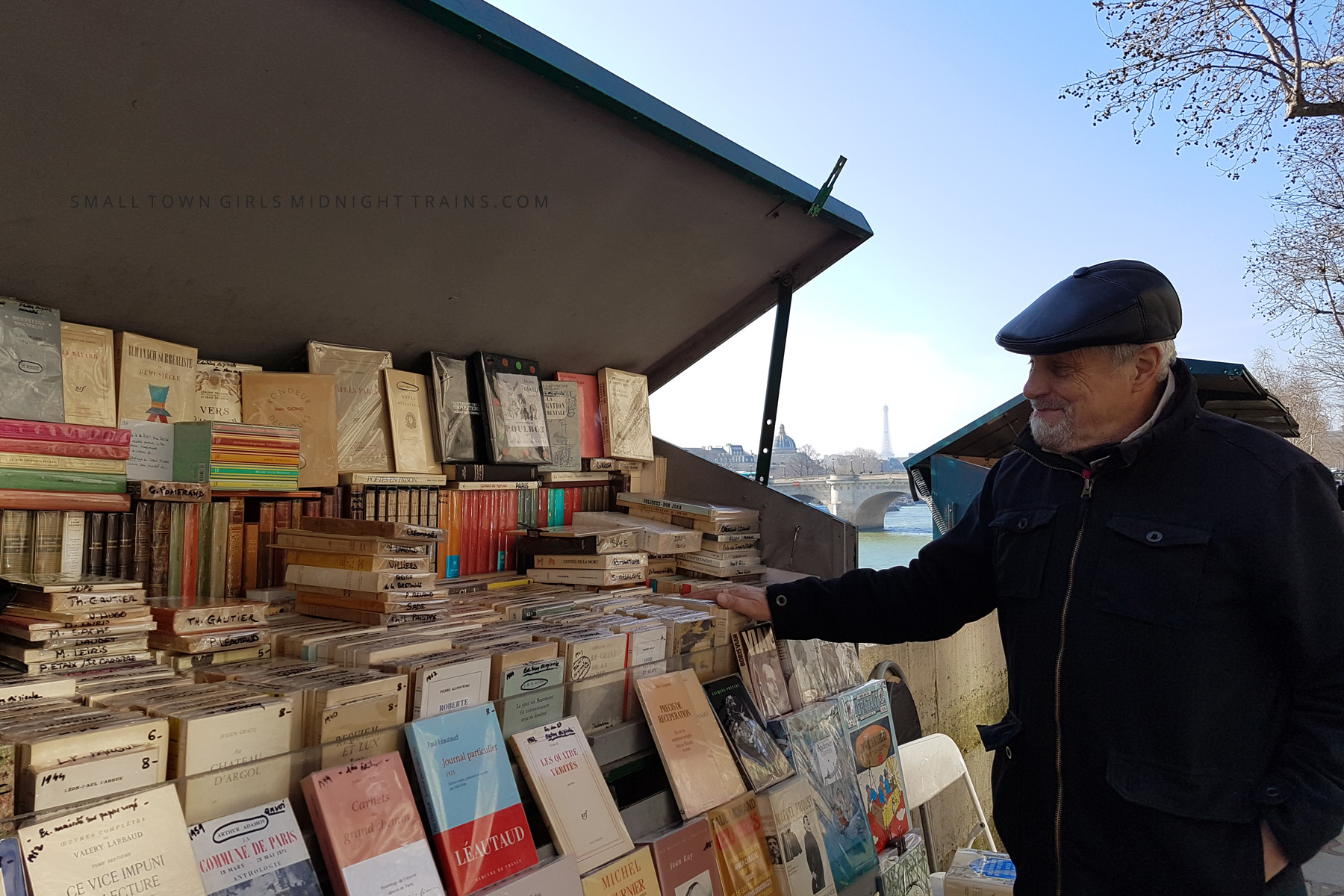

In Paris, near the Cathedral of Notre Dame, you will see a row of green metal boxes lining both banks of the River Seine. These are the stalls of the bouquinistes, antiquarian traders of books whose history stretch all the way back to the 16th century.

A romantic version of their origins recounts that a ship carrying books sunk near the cathedral. The sailors, anticipating lost income, salvaged as much of their cargo as they could and sold them (and I guess found it profitable enough to continue). The more staid — and more likely true — story is that they started out as itinerant book peddlers. Small trade at first. Low respectability. Business boomed, however, during the French Revolution as books from ransacked churches and chateaus changed hands at a sort of riverside black market. The bouquinistes have been a fixture of the Seine since then, the wheelbarrows they used to transport their wares transformed into the iconic green boxes that are included in UNESCO’s recognition of the riverbanks as a World Heritage Site.

.

.

Last February, after lunch with my new friend Christian, we resumed our walk towards Notre Dame and I mentioned I was on a mission to buy a book from a bouquiniste.

“You know,” he said, “if you want a book, you can buy one at a much cheaper price in a bookstore.”

But I wanted a book from a bouquiniste for a reason.

Legend has it that not only were the bouquinistes business-savvy itinerants, they were also bit players during certain dramatic events in France’s long history. In the French Wars of Religion, for example, the bouquinistes were said to secretly pass along Protestant pamphlets, a risky undertaking in then Catholic Paris. And during World War II, the booksellers contributed to the cause of the French Resistance by carrying coded messages in the pages of their books and consenting to have their green boxes used as dead drops.

I meant to buy a book from them as a sort of tribute, a nod to their intrepid past. I also wanted to help them fight, if only in a symbolic way, a much more present threat: dwindling sales.

By decree, bouquinistes must sell only books in 3 out of the 4 boxes allowed them by the government. Only one box may contain commercial goods and yet ironically it is often this box — usually filled with fridge magnets, key rings, and other trinkets — that keeps the seller warm, clothed and fed. In the age of e-books and the internet, there just aren’t that many people anymore who turn to the Seine when they’re in need of a title. Customers, these days, tend to be tourists.

In fact, my first encounter with a bouquiniste was back in 2011, when I approached one to buy a set of coasters as a souvenir. I remember the old man’s kind smile as I verified the price in halting French — 4 for 10 euros, if I recall correctly. They were lovely coasters, vintage prints, and I still use them — there’s one on my desk right now — but when I read about the bouquinistes’ tradition-versus-roof-over-head dilemma, I regretted not buying a book.

Which isn’t to say that I told all this to my well-meaning new acquaintance. I simply gave him the short version: that I’d told my sister the story of the bouquinistes and she’d asked me to buy a book in French for her.

.

.

Want to get a smile out of a bouquiniste? Ask them if they have a copy of Le Petit Prince.

The first bouquiniste we approached, a young lady in a leather jacket and heavy eye shadow, said “No, I’m sorry” with an undertone of amusement.

I said, “I’m not the first person to ask you that today, am I?” and she laughed.

The second confirmed Saint-Exupéry’s popularity. “Everyone asks me if I have The Little Prince. The Chinese. The Japanese. All the tourists. I rarely have The Little Prince and when I do it is snapped up immediately.”

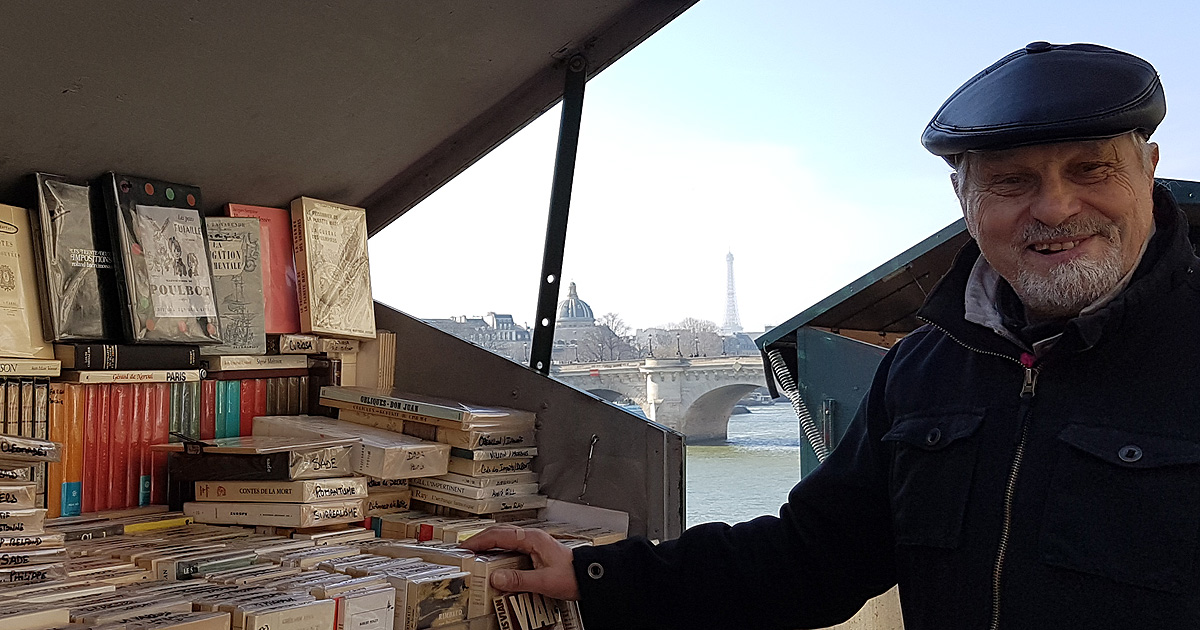

The second bouquiniste was an older man named Jean and he was wearing a beret, a detail Christian noted right away.

“Take a picture from here!” He said eagerly, pointing to a spot on the ground. “Look, take a picture here and you will have the Eiffel Tower, the dome, a bouquiniste stall, and a French man wearing a beret. It doesn’t get more Parisian than that.”

.

.

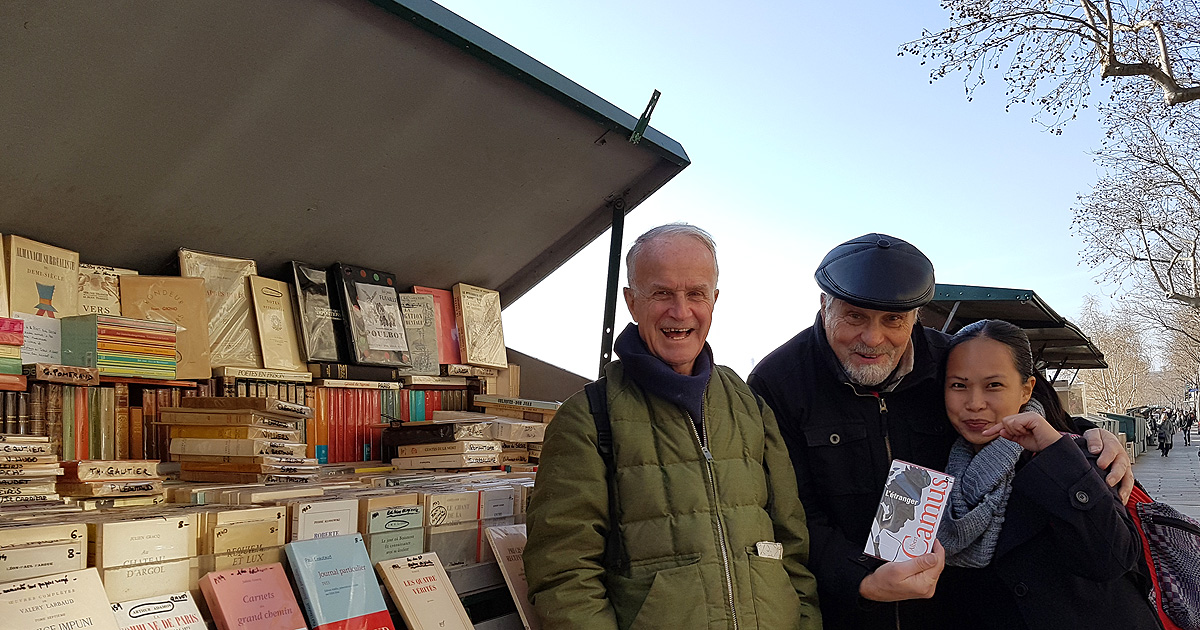

While I took said picture, the two of them began to discuss in earnest what sort of French book in French would suit someone who didn’t actually know French. They practically went over the entire stall.

“How about this?” Jean the bouquiniste would propose and Christian the retired schoolteacher would consider for a moment then shake his head and say, “No, no, the language there is too idiomatic, she will not be able to understand” or a similar objection.

“How about this? The language here will be easy to understand.”

“Yes, but the author is not French.”

At one point, I asked Jean if he had a book on the sea. “My sister’s an oceanographer,” I explained.

“Hmmm. How about this?” He held up a Moby Dick.

But even as I struggled with how to say that Moby Dick wasn’t exactly what I had in mind — I was thinking more of a science textbook — Christian was already shaking his head. “No. Melville. American, not French.”

I spotted a Chesterton and reached for one, thinking I might buy it for myself, but Christian immediately said, “British.” (Me in my head: “I knew that!”)

Christian added sadly, “It would have been so much easier if he had The Little Prince.”

“Well, how about this?” Jean said, holding up another book.

And so it went on and on (and on) as I observed in secret delight. I thought, in the end, it wouldn’t matter so much to my sister what book I eventually bought. She would be more pleased at the thought that two strangers were taking such trouble to decide what book would be perfect for her.

.

.

These days, it’s perfectly possible to learn all about a place and explore its byways without actually being there. I’ve gone on tours where nearly everything a guide said I’d previously read on Wikipedia. Thanks to Photoshop, the pictures you find online can be more breathtaking than their actual subjects.

But moments of magic — I have no other word for it — these are what make travel worthwhile.

When the road springs surprises on you — such as two gentlemen you never knew existed till that afternoon arguing about what book you should buy for your sister — and it’s better than anything you could have planned for, that’s travel’s raison d’être right there.

You have to allow it to happen though. You have to give life the opportunity to delight you.

Imagine if I’d packed my schedule so tight that “buy a book from a bouquiniste” was only allotted 5 minutes.

Imagine if I’d simply gone to the bookstore.

.

.

.

This is the best, real life description of traveling in Paris I have ever read. Really.

That’s a very nice thing to say! Thank you very much.

What a lovely story Gaya. And I know exactly what you mean about these kinds of encounters. They’re the most precious of travel moments. And I love your new blog layout. Fabulous!

Alison xo

Thank you Alison! And yes — when I look back on trips, these are the moments that stand out. xx

“You have to give life the opportunity to delight you.” Yes…this right here…Yes!

That whole day still amazes me. I’m a bit of an introvert so I didn’t really expect encounters like that. Life can be generous with its surprises.

A travel is certainly worthwhile. The very pleasure of being there!

Very true.

Hi Ate Gaya. I’m Lei’s friend. This story makes me want to travel and get lost again. Thank you! =)

Hi Ethel! Thank you for taking the time to leave this comment. It made my day. 🙂 Happy travels!